Juniper Publishers-Open Access Journal of Case Studies

Three Patients with Dysphagia Following Hospitalization and Respiratory Support for Severe COVID-19 Pneumonia

Authored by Layal A Olaywan and Ralph M Nehme

Abstract

Background: During the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, patients with severe pneumonia may require hospitalization and respiratory support. Oropharyngeal dysphagia may occur due to lack of muscle coordination of the respiratory and swallowing mechanisms in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) or as a consequence of intervention for respiratory support. This report is of a series of three patients who were hospitalized for severe COVID-19 pneumonia who developed dysphagia.

Case Series: Three patients patients were diagnosed with severe COVID-19 pneumonia with positive reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing for SARS-CoV-2. Case 1: A 69-year-old man hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia and who underwent noninvasive mechanical ventilation followed by difficulty in swallowing. Case 2: An 84-year-old woman hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia and developed confusion, disorientation, swallowing difficulties, and aspiration pneumonia. Case 3: An 87-year-old man who developed ARDS following hospital admission with COVID-19 pneumonia.

Conclusion: These cases have shown that dysphagia may develop in patients hospitalized with severe COVID-19 pneumonia, either due to respiratory interventions or due to ARDS, and should be identified and actively managed to prevent further complications due to aspiration of gastric contents.

Keywords: Coronavirus disease 2019; COVID-19; Dysphagia; Pneumonia; Case report

Introduction

With more than 150 million cases to date and 6.93 million global deaths [1], COVID-19 has massively modified and overwhelmed the structure of the healthcare system worldwide, requiring persistent novel approaches for healthcare delivery [2,3]. The most common clinically reported presentation of severe COVID-19 cases is acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (67% of COVID-19 patients with the severe illness) [3], rapidly progressing to multi-organ failure and death [4]. Some of these patients require intubation and mechanical ventilation.

However, post-extubation dysphagia is a common concern in intensive care unit patients with prevalence ranging between 3 and 62% and is significantly associated with increased intubation time [5,6]. Dysphagia can be related to multiple etiologies attributed to cognitive and mechanical changes [7]. Intubation has been shown to cause laryngeal damage in 83% of cases with 47% incidence of full-thickness tracheal erosion (FTTE) and tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF) [8] with only a few intubated patients being spared from injury [9]. Additional collateral damage in COVID-19 patients may be attributed to the necessity of rapid intervention in emergency cases and the difficult delivery of care in personal protective equipment [10]. In regard to cognitive etiologies, critical illness is an important predictor of impaired swallowing reflex coordination [7]. This reflex may be further weakened in COVID-19 patients having incoordination between swallowing and respiration, and in whom central and peripheral nerve involvement is already proven [11-13]. According to recent findings, dysphagia in COVID-19 positive patients was thought to be related to the lack of the respiratory-swallowing coordination seen in ARDS or due to mechanical respiratory support damage [11]. In addition, during this pandemic, there has been several case reports associating COVID-19 infection with Guillain Barre Syndrome, a disease that is manifested by an acute ascending weakness and sometimes dysphagia, and that the weakness was more severe in COVID-19 infected patients necessitating ICU admission. This disease can also contribute to the appearance of dysphagia in some COVID-19 positive patients [14].

Metabolic and nutritional adverse effects of COVID-19 infection may also contribute to the delayed recovery from dysphagia in critically ill patients, which usually holds unfavorable outcomes and late results. Dysphagia and consequently loss of appetite and worse nutritional status as adverse effects of COVID-19 infection may also contribute to negative prognostic factors when underestimated, holding unfavorable outcomes for COVID-19 patients [15,16].

To date, multiple cases of dysphagia following COVID-19 have been reported and were associated with poor outcomes such as aspiration pneumonia, increased length of hospitalization, and prolonged periods of rehabilitation [11]. In light of high associated mortality rates and with little data on appropriate management, the study of dysphagia in COVID-19 patients can contribute to the development of prompt evaluation and intervention procedures done in a multidisciplinary context including speech and language therapy assessment, practice swallow, progressive modifications of diet textures and adaptation to environmental factors to better predict patient recovery and optimize rehabilitation helping them return to their baseline swallow function.

This report is of a series of three patients who were hospitalized for severe COVID-19 pneumonia who developed dysphagia.

Case Series

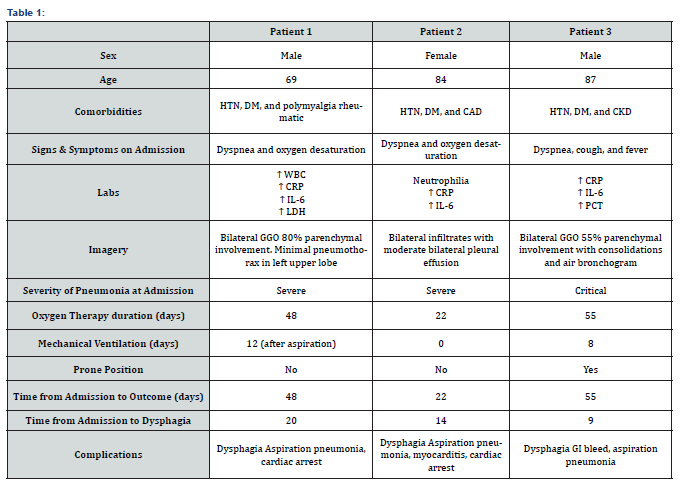

We present a series of three cases of dysphagia in COVID-19 patients collected retrospectively from a single university hospital in Beirut. Patients included in the study presented between December 2020 and January 2021. Biographical details are described in Table 1. Pneumonia was classified as critical if the patient required mechanical ventilation and severe if he required noninvasive ventilation. Diagnosis of COVID-19 in each of the three patients was confirmed by two positive nasopharyngeal specimens on RT-PCR collected one week apart. PCR kit Name: Gene finder COVID-19 fast RealAmp kit. Manufacturer: OSANG Healthcare, Korea

Case 1

A 69-year-old male was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for dyspnea and oxygen desaturation due to severe COVID-19 pneumonia that required several days of noninvasive mechanical ventilation (NIV). After three weeks, even though noninvasive ventilation was gradually tapered to high flow nasal cannula the patient showed some difficulty swallowing food. Assessment using a fibroscopic examination showed normal anatomy with normal movement of vocal cords but sensation was found to be abnormal accompanied by extreme weakness and salivary accumulation in the pharynx with difficulty swallowing it. CT of the brain showed no abnormalities. Patient was switched to parenteral nutrition and he was put nil per os to avoid further aspiration.

A few days later, the patient manifested an increase in oxygen requirement and increased dyspnea. CT of the chest was repeated and showed right upper lobe consolidation and bilateral lower lobes consolidations that are possibly due to aspiration pneumonia. He was started on antibiotics, but he deteriorated clinically, got intubated and eventually died seven weeks after admission.

Case 2

An 84-year-old female was admitted to regular floor for dyspnea and oxygen desaturation due to severe pneumonia caused by COVID-19 infection. She required several days of 15L/minute oxygen delivery by nonrebreather face mask, she was not mechanically ventilated.

Two weeks later, the patient had worsening dyspnea and an increase in oxygen requirements. Transthoracic echocardiography showed type I diastolic dysfunction with an ejection fraction (EF) of 45% and a systolic pulmonary artery pressure (sPAP) of 40mmHg. Coronarography was done and showed no coronary artery stenosis. Her condition was further complicated by confusion, disorientation, swallowing difficulties, and aspiration pneumonia. Brain MRI showed atrophy with no acute infarcts or ischemic changes. The patient required a gastrostomy tube for feeding. But the patient deteriorated and death occurred three weeks after admission.

Case 3

An 87-year-old male was admitted to the ICU for confirmed severe COVID-19 pneumonia with dyspnea, cough, and fever. The patient required oxygen supplementation with a high-flow nasal cannula then got intubated for ARDS. His condition was complicated by a gastrointestinal bleed requiring multiple units of blood transfusion.

One week later, the patient showed recovery, was extubated to a nasal cannula of 3/L min oxygen and was transferred to the regular floor. On the twelfth day after admission, the patient complained of dysphagia, he developed fever and cough with expectoration, and had an increase in oxygen requirements. Chest X-ray showed new left-sided pneumonia requiring therapeutic bronchoscopy and removal of mucus plugs. An otorhinolaryngologist was consulted for the assessment of oropharyngeal dysphagia. GAG reflex was absent bilaterally. Fibroscopy was done which showed negative epiglottic tactile sense, laryngeal reflex, or swallowing reflex. A jejunostomy tube was then inserted, and the patient was discharged from the hospital on enteral nutrition, with persistent dysphagia eight weeks after admission (Table 1).

Discussion

Swallowing is a sequential and coordinated developmental behavior connecting more than thirty muscles and six cranial nerves [17,18]. If disrupted, a wide range of symptoms may occur resulting in adverse patient outcomes, such as malnutrition, aspiration pneumonia, prolonged hospitalization, and death [6,19]. Most people with dysphagia also report a substantial decrease in their quality of life influencing their eating behaviors and psychological well-being [20].

The studied patients were elderly with various comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and inflammatory diseases which explains the severity of their COVID-19 condition and the necessity of intensive care unit admission [21]. Dysphagia in ICU patients has been previously related to multiple etiologies, ranging from traumatic upper airway injury to neurological abnormalities [7].

In fact, dysphagia is a common symptom that accompanies a number of neurologic disorders since it needs meticulous neural coordination within a network of interneurons located in the brainstem, hence called neurogenic dysphagia [22]. In fact, the first patient demonstrated abnormal sensation and prominent weakness, which are two important mechanisms in the development of ICU dysphagia. As suggested by Zuercher et al. [6] & Brodsky et al. [23] specific swallow-related muscular weakness and reduced local sensation are key components of dysphagia and important predictors of aspiration pneumonia, hence the exacerbated condition of the patient [6,23]. It is important to note that all patients had elevated IL-6; this can reflect a level of neuroinflammation and blood-brain barrier dysfunction in patients with COVID-19, supporting the hypothesis of neurogenic dysphagia [24]. These findings go along with the neurologic deficits correlated with both ARDS and ICU practices that are necessary in the treatment of COVID-19 patients [11].

Our second patient also showed symptoms of dysphagia of neurologic origin that could not be explained by a stroke event which is the most common cause of neurogenic dysphagia [25]. This hypothesis is further strengthened by associated findings of delirium, another known cause of dysphagia, and MRI results showing acquired brain injury, probably due to lack of oxygen in this patient. In fact, studies suggest that delirium is an important predictor of dysphagia and aspiration in hospitalized elderly patients [26]. Hence, we can conclude that there might be several mechanisms responsible for dysphagia in one patient, especially the elderly ones.

All findings can also be explained by the increasing evidence of central nervous system implication in COVID-19, notably brain stem involvement [27,28]. These effects arise from the established direct neurotrophic effect of the virus or by a post-infectious autoimmune mechanism [29]. Interestingly, Matschke et al. [30] postulated that cranial nerve involvement may be associated with symptoms of dysphagia found in COVID-19 patients, implying glossopharyngeal and vagal effect on bulbar muscle dysfunction resulting in dysphagia, although brainstem neuropathological findings were not found in the post-mortem period [30]. Moreover, the various multisystemic effects of COVID-19 on elderly ICU patients may favor a decompensated state hence the development of critical illness polyneuropathy with accompanied dysphagia [31].

Aside from the neurological background, the risk of dysphagia is further increased in patients who require mechanical intubation and/or tracheostomies. Post-extubation dysphagia is more likely to occur with prolonged intubation time, but can still occur with a few days of intubation [32]. A higher incidence of dysphagia was reported when intubation was upon emergency admission, which leaves room for more laryngeal trauma upon insertion of the tube, especially in COVID-19 patients in whom prudent techniques should be adopted [33]. This can explain the development of aspiration in the third patient, in whom aspiration pneumonia occurred due to dysphagia and exacerbated his condition. This hypothesis is further reinforced by the concomitant presence of a neurologic etiology in this patient explained by the abnormal reflexes. Similar mechanisms explain the development of dysphagia in the fourth patient, in whom the need for reintubation and rapid decompensation led to death. In fact, aspiration pneumonia endotracheal obstruction and impaired mucus clearance may be exacerbated by prone-position of mechanically ventilated, a therapeutic intervention that is widely used in COVID-19 patients used to optimize oxygenation leading to atelectasis and pneumonia [11]. In addition to that, critically-ill patients are strong candidates for myopathy and polyneuropathy, further complicating their illness, compromising their rehabilitation, and prolonging their ICU stay [34,35].

Bacterial co-infections need to be taken into consideration since intensive care unit patients are at a greater risk for nosocomial infections and these infections are major predictors of severity and poor outcome in COVID-19 patients [36,37]. These findings are similar to those in Dziewas et al. [37] in which patients with dysphagia frequently had superimposed bacterial infections causing additional major pulmonary complications [37].

This highlights the importance of thorough diagnostic and management procedures starting from clinical screening protocol as bedside assessment which is less costing and time consuming to video fluoroscopic assessment of swallowing when available because of the need to transfer the patient to the radiological department to predict and anticipate treatment of oropharyngeal dysphagia because once set, the progression to aspiration pneumonia is “silent” and life-threatening [38]. A Taking into account that the diagnosis of dysphagia in COVID-19 patients is not always obvious and gold-standard diagnostic methods can’t be relied on, familiarity and attention should be improved among physicians [39].

Various treatment modalities of dysphagia in COVID-19 patients have been explored and showed interesting results. A recent case study reported a favorable restoration of safe swallowing function in a patient with COVID-19 post-extubation neurogenic dysphagia using pharyngeal electrical stimulation, a method formerly used for dysphagia of stroke origin [40]. This method can be used to accelerate recovery and reduce total hospital stay. The use of speech and language therapy (SLT) also showed favorable results in rehabilitation of COVID-19 patients with dysphagia and dysphonia after ICU stay [41].

Conclusion

The main finding in this case series is that dysphagia is putting COVID patients at higher risk of airway compromise. Dysphagia may develop in patients hospitalized with severe COVID-19 pneumonia, either due to respiratory interventions or due to ARDS, and should be identified and actively managed to prevent further complications due to aspiration of gastric contents. This complication is responsible for prolonged hospitalization and even poor overall outcome. There is still a need for large-scale prospective studies to determine optimal early diagnostic and management procedures in these patients. In the absence of established standard guidelines, the key element is the need for optimization of systematic dysphagia screening in ICU COVID-19 patients and targeted swallow rehabilitation methods. Due to the limited information currently available, the concomitant presence of both pathologies remains a major challenge for ICU physicians.

To know more about Juniper Publishers please click on: https://juniperpublishers.com/manuscript-guidelines.php

For more articles in Open Access Journal of Case Studies please click on: https://juniperpublishers.com/jojcs/index.php