Juniper Publishers- Open Access Journal of Case Studies

Mammography Appearance of Filariasis - A Case Study

Authored by Biren A Shah

Abstract

Filariasis of the breast, most commonly caused by a roundworm in the Filarioidea family, Wuchereria bancrofti, can have pathognomonic findings of breast calcifications on mammography that may be confused with other calcifications associated with malignancy. The purpose of this report is to describe a classic presentation of breast filariasis on mammography and distinguish it from other malignant calcifications of the breast.

Keywords: Filariasis; Parasite; Mammography

Introduction

Lymphatic filariasis is typically a benign infection caused by Wuchereria bancrofti, native to tropical countries like Nigeria, India and Indonesia [1]. This parasite is transmitted by mosquitoes and black flies that carry larvae from one human host to the next. The larvae enter the bloodstream, infiltrate and obstruct the lymphatic vessels, and cause potential vascular extravasation of the parasite into mammary tissue and later become calcified [1].

Patients may present with palpable, tender, mobile, firm, and benign lumps on the breast and “serpiginous calcifications” on mammography [2]. Though the presentation of this infection in the breast is uncommon, it is increasing in developed countries as people immigrate from areas where filariasis is endemic [2]. Active filariasis is conventionally diagnosed by peripheral blood smear and, sometimes by fine needle aspiration, these calcifications can indicate the presence of a past or current infection [3].

Case Presentation

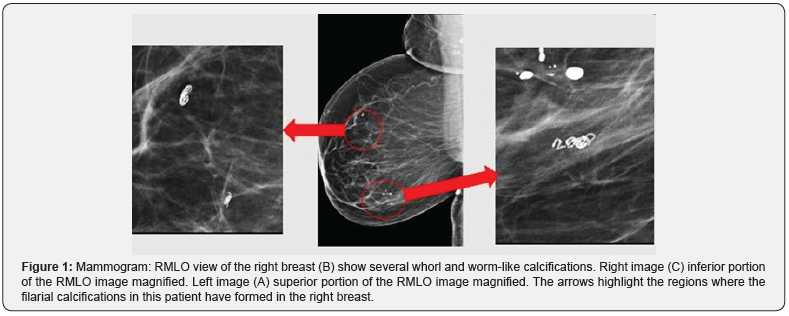

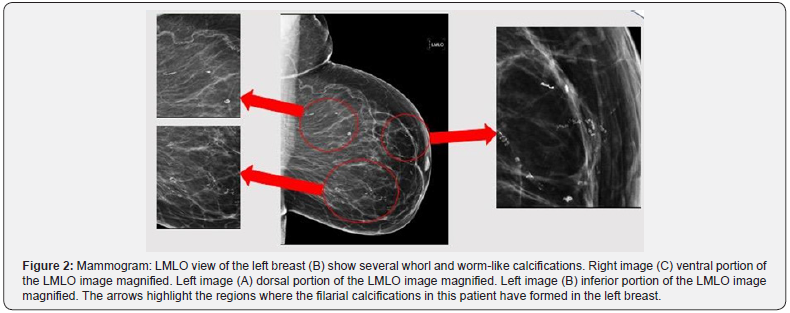

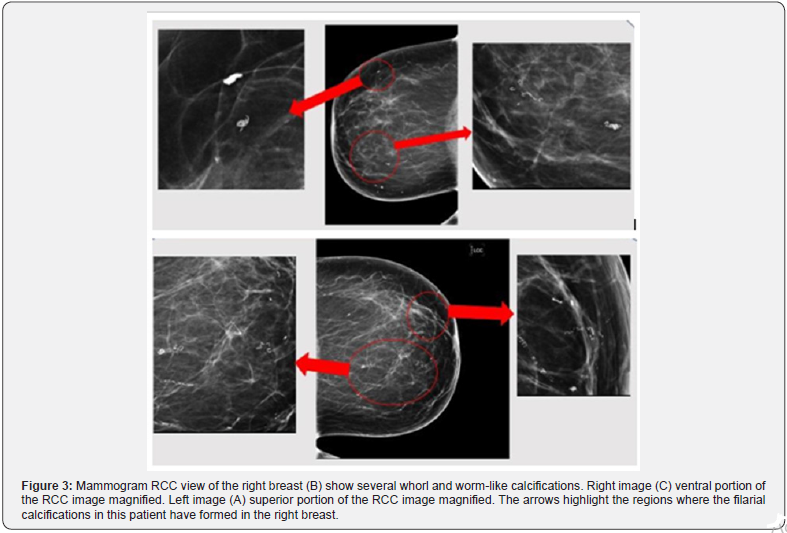

62-year-old Nigerian female for a bilateral screening mammogram (Figures 1-4).

Discussion

Filariasis is caused by a nematode infection, most commonly by Wuchereria bancrofti, transmitted by blood feeding arthropods, mainly black flies and mosquitoes. The existence of lymphatic filariasis and the classic presentation of elephantiasis dates back as early as 1500 B.C. documented by the ancient Egyptians, Hindus, and Persians [4]. Filariasis affects the lymphatic system and, in chronic cases, can cause severe lymphedema, elephantiasis, pain, and disability [5]. “In 2000, over 120 million people were infected in 52 countries worldwide, with about 40 million people disfigured and incapacitated by the disease” [5].

Although this infection can have an asymptomatic, acute and chronic presentation, breast involvement is most commonly a sequelae of chronic infection [5]. Though uncommon, filariasis of the breast can present as a tender, palpable breast mass with possible filarial granuloma and worm-like calcifications [6]. The filarial calcifications in particular can be present in any location in the breast, as depicted in the findings of our patient [6]. In addition to the classic tortuous, ring-like calcifications, the location of the calcification can further differentiate the different nematode infections of the breast. For example, Wuchereria bancrofti is found in the breast parenchyma while other infections like onchocerca volvulus are found just beneath the skin and in lymphatic vessels and nodes [6].

In this case, the patient presented with several fine-beaded, whorl-like, serpentine, and vermiform lesions caused by the calcification of the dead parasite in the breast parenchyma. In active forms of the disease, these calcifications can be accompanied by inflammatory changes that include a “peau d’ orange” edema of the skin and enlarged lymph nodes that can sometimes mimic inflammatory carcinoma [6]. This patient’s condition was only remarkable for her breast calcifications without inflammatory changes and was asymptomatic indicating an inactive form of the disease process.

Breast calcifications are common findings detected on routine mammography that can be associated with several benign and malignant pathologies [7]. In the case of filariasis, the worm-like, serpiginous calcifications can occur many years after exposure to the parasite and are benign findings on mammography [7]. Understanding this kind of filarial breast calcification and its appearance on radiographic imaging, can discriminate suspicious calcifications requiring biopsy from those that are benign [7]. Our patient’s serpiginous calcifications were detected on routine mammography screening and the patient was asymptomatic. Once these findings were determined to be filarial calcifications of the breast, no further work up was conducted.

In the event that a patient presents with these mammographic findings and symptoms of acute infection including lymphedema and several inflammatory changes, the conventional mode of diagnosis is a peripheral smear [8]. Blood collection should be done at night as lymphatic filariasis circulate in the blood with nocturnal periodicity [8]. Serologic techniques measuring anti-filarial IgG4 in the blood can diagnose patients with active infection [8].

In countries where filariasis is endemic, the primary goal of treatment is to eliminate microfilariae infected individuals to prevent the transmission of the disease [5]. According to the WHO, a single dose administration of diethylcarbamazine citrate (DEC) and albendazole is 99% effective in removing microfilariae from the blood for one year after treatment [5]. Understanding the radiographic findings, diagnosis, treatment and prevention of this diseases, particularly the rare manifestations like the breast calcification, can prove to be very beneficial in a clinical setting. With the increasing immigrant population from India and Africa here in the United States, recognizing the benign nature of this radiographic imaging will eliminate unnecessary testing for diagnosis.

For more articles in Open Access Journal of Case Studies please click on: https://juniperpublishers.com/jojcs/index.php

No comments:

Post a Comment