Juniper Publishers- Open Access Journal of Case Studies

When Magnetic Resonance Imaging Cannot be Missed for Evaluation of Pediatric Seizures

Authored by Tarik Zahouani

Introduction

Brain tumors (BT) account for nearly 25% of all cancers in children and have the highest mortality rate of all pediatric malignancies [1,2]. Seizure is a common presenting symptom of pediatric brain tumors, but brain tumor remains a rare cause of epilepsy in childhood [3]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) stands as the best diagnostic imaging modality. We present three cases of brain tumors presenting with seizures and diagnosed with MRI.

Case Presentation

Case 1

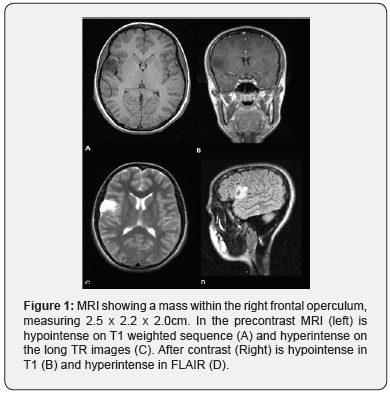

A 12 y/o female presented an episode of loss of movement of her left hand, associated with asymmetry and twitching of the face, slurred speech, minimal drooling and decrease in strength. Afterwards, the patient lost her consciousness and was found unresponsive with her eyes rolled back. Upon arrival to the emergency department (ED), she was alert, oriented with non-focal neurological examination. She was subsequently admitted and received Levetiracetam 500mg every 12 hours. The electroencephalogram (EEG) showed generalized seizure activity. The MRI revealed a cortical mass in the right frontal operculum likely to be Glioma or Dysembryplastic Neuroepithelial Tumor (DNET) with associated focal cortical dysplasia (Figure 1).

Case 2

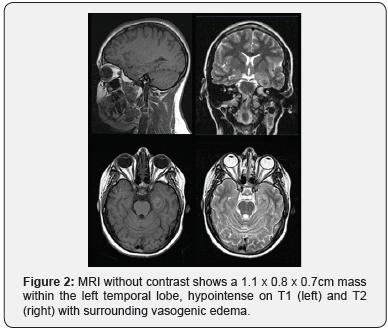

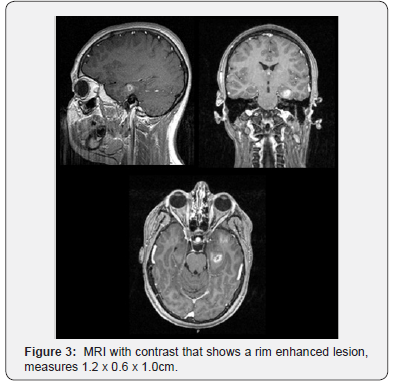

A 14 y/o female presented with her first unprovoked seizure. When she awoke, she had stiffness and generalized body movements, with associated tongue and lip biting, but without incontinence. This episode lasted one minute, and after its resolution she felt sleepy and drowsy. Physical and neurological examination were unremarkable. She was admitted for further investigation. The EEG showed normal electrical activity. The patient was started on levetiracetam extended release 1000mg daily and remained seizure free. The MRI showed a mass in the left temporal lobe (Figure 2), hypertrophy of the parahippocampal gyrus and an irregular rim-enhancing mass (Figure 3), consisting with neoplasm, toxoplasmosis, neurocysticercosis, tumefactive demyelination, abscess, primary malignancy, or less likely metastatic disease. Patient underwent to neurosurgery for removal of the mass and symptomatically improved with normal follow up neurological exams. The pathology report showed a glioma most consistent with polymorphous low grade neuroepithelial tumor of the young.

Case 3

An 18 y/o male presented to the ED after two seizure episodes. He had multiple episodes of seizures for one year and was non-compliant with Phenytoin treatment. In the ED the patient was alert, active and in no acute distress, with a normal neurological exam. The patient was admitted in the pediatric inpatient unit and received a loading dose of Fosphenytoin and started on a maintenance dose of Valproic acid. During hospital admission the X-ray of his right shoulder showed Hill-Sachs deformity, consistent with prior anterior shoulder dislocations. The MRI revealed a cerebral mass in the right temporal lobe, likely to be neoplasm, neurocysticercosis or encephalomalacia from prior trauma. On the follow up visit, he rejected the surgical approach and elected to follow the lesion.

Discussion

Seizure is the most common neurologic disorder in childhood and accounts for about 13% of pediatric brain tumor presentation. The exact relationship between BT and seizures is poorly understood [3]. BT are the deadliest of all pediatric malignancies and their incidence is second only to hematologic malignancies [2]. They are often low-grade lesions such as DNETs, gangliogliomas, and low-grade gliomas. While DNETs and gangliogliomas almost exclusively present with seizures, gliomas may also produce focal neurological deficits secondary to mass effect and cerebral edema. The most common locations for brain tumors causing epilepsy are in the temporal lobe and the perirolandic region [4]. MRI is by far the best diagnostic method to detect brain tumors with a maximum specificity and sensitivity [5].

The availability of high-quality MRI allows for an in vivo view of pathological anatomy as well as detection of lesions such as migration defects and mesial temporal sclerosis, both of which are known causes of childhood onset seizure. These two abnormalities are not readily seen on computed tomography (CT). MRI can also detect brain lesions in patients who had a normal CT [6].

The International League Against Epilepsy recommends neuroimaging with an MRI for all epileptic patients who do not have a definitive identifiable idiopathic epilepsy syndrome [6]. MRI is also recommended for children who develop epilepsy before 2 years of age or in whom seizures continue despite first line drug treatment [7].

The EEG can be useful in suggesting a structural abnormality, especially in children with simple and complex partial seizures; however, the correlation between focal EEG findings and structural lesions is neither close nor consistent [8].

Our patients presented with seizures and EEG did not suggest a structural abnormality, hence the indication to perform MRI which made the diagnosis. This gives us confidence in ordering MRI study even if neurological examination is unrevealing and EEG is normal. Head CT would have been not diagnostic.

Conclusion

Seizure is a common presentation of brain tumors in children, and is rarely accompanied by focal neurological signs, particularly in older children. Neuroimaging with MRI should be undertaken routinely for epilepsy when seizures had their onset in the first two years after birth, have focal features and when EEG is unrevealing.

For more articles in Juniper Publishers | Open Access Journal of Case Studies please click on: https://juniperpublishers.com/jojcs/index.php

No comments:

Post a Comment