Juniper Publishers- Open Access Journal of Case Studies

A Neurological Presentation of Intravascular Large B-cell Lymphoma: a Rare Cause of Multi-Territory Strokes

Authored by J Newman

Abstract

Intravascular Large B-Cell Lymphoma (ILBCL) affects one in a million people. Here it presented as dysphasia and leg weakness in a forty-five-year-old woman with a history of mental health issues. The initial investigations showed multi-territory infarcts for which we were unable to find a treatable cause. Her condition progressed and she unfortunately died. Although rare, ILBCL ought to be included in differential diagnoses of multi-territory strokes, however, the diagnosis is commonly made post-mortem. Here we discuss common presentations of ILBCL. We note the proximity of her worsening psychiatric symptoms to the time of her death.

Keywords: Lymphocyte cells; Psychiatric symptoms; Intracerebral haemorrhage; Neurological manifestations; Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma

Introduction

Intravascular Large B-Cell Lymphoma is a rare subset of Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma that involves the pathological proliferation of lymphocyte cells within capillaries and other small blood vessels [1], causing their occlusion.

As the clonal proliferation is intra-vascular there is relative sparing of the surrounding tissue, making it more difficult to diagnose. The presenting symptoms vary according to the organ affected, although the skin and nervous system are common. When occlusion occurs intra-cerebrally the result is often a stroke.

The importance of identifying the aetiology of stroke in the afflicted patient is well recognised, as it can help direct management and treatment. This is particularly relevant to patients with multi-territory strokes, recurrent strokes, and those who are affected at a young age.

Our patient had worsening psychiatric symptoms leading up to her final admission and diagnosis. We note the proximity of these events, as psychiatric symptoms of ILBCL are poorly documented.

Case Report

A forty-five-year-old Caucasian woman was seen in the emergency department at a tertiary hospital in the UK. She presented with a two-day history of mumbling speech and acting withdrawn, left-sided leg and facial weakness, and right arm spasms. She had a background of depression and had presented acutely to community and hospital psychiatric services 5 months prior to this admission (we do not know the nature of that presentation). Her current medication included olanzapine 10mg daily and venlafaxine MR 300mg daily. Initial examination demonstrated an up-going right plantar response but no other focal neurology.

A CT head scan revealed low attenuation signal changes in the right cerebellar and right frontal lobes. Although her presentation appeared more psychiatric than organic, she was kept in to investigate her symptom complex and CT findings.

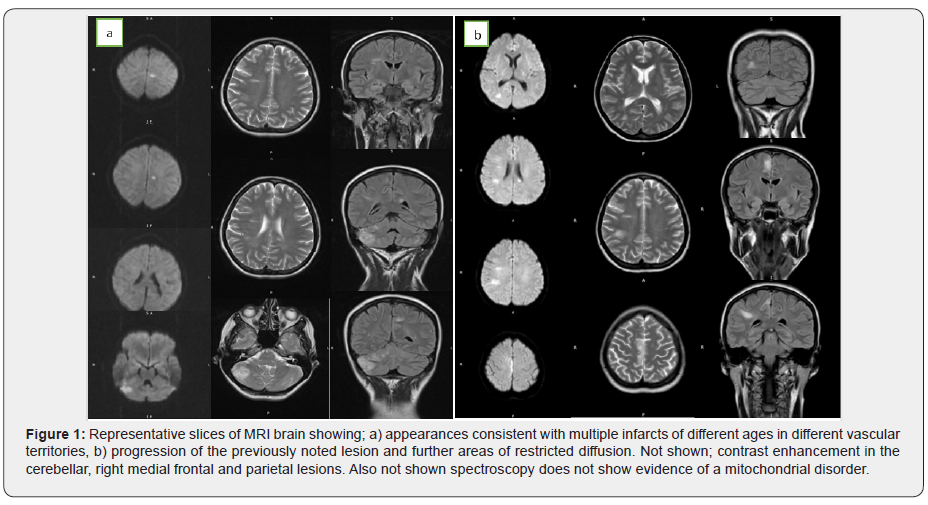

A subsequent MRI head demonstrated multiple areas of restricted diffusion in different vascular territories (Figure 1a). There were also foci of high T2 signal changes in the supra-tentorial white matter, with some demonstrating restricted diffusion. Considering the different territories, and different ages of these lesions, a cardio-embolic source was the most likely cause of these infarcts. Her trans-thoracic echocardiogram (TTE) was normal, as was her carotid Doppler. A lumbar puncture showed normal CSF. At this point she developed episodes of seizures corroborated by EEG.

We undertook investigations for lymphoma, and the blood tests showed little except a raised lactate dehydrogenase (LDH 400iU, plasma viscosity normal, blood film normal, haemoglobin 115g/L). We also discussed the possibility of vasculitis. However, her blood results and MR Angiogram did not show any positive findings.

A full-body CT scan was performed to look for other neoplastic lesions, but this was normal. We started high-dose corticosteroids as an empirical treatment for vasculitis.

Two weeks after this, she started to deteriorate. Her seizures became more frequent and her dysphasia more pronounced. A repeat MRI brain (Figure 1b) showed an increase in size of the lesions in the medial frontal and parietal lobes. New lesions in the corpus callosum and left thalamus showed restricted diffusion. The cerebellar, right medial frontal and parietal lesions enhanced with contrast. Long- and short-term MRI head spectroscopy did not show any evidence of a lactate peak to suggest mitochondrial disorder. This picture was consistent with a diagnosis of vasculitis.

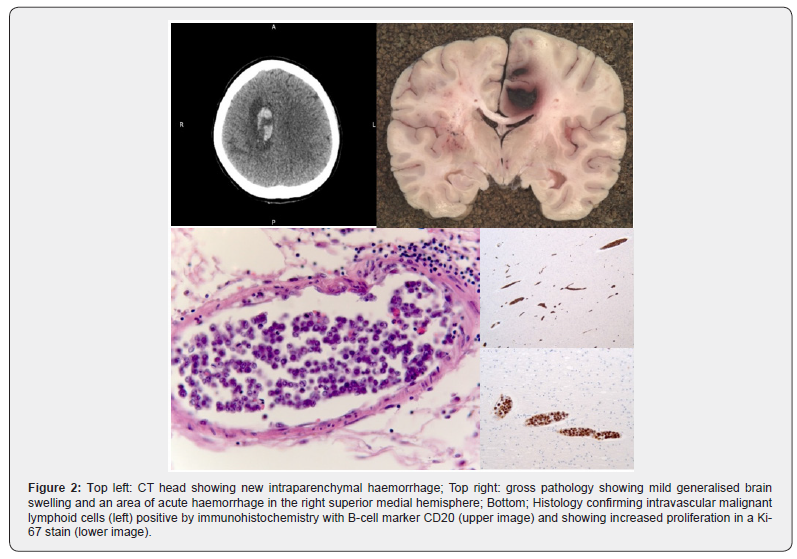

Her condition continued to decline. Her GCS dropped to 7 and did not fluctuate, a repeat CT head revealed a right-sided intracerebral haemorrhage (Figure 2). Given the multitude of insults and progressive nature of her symptoms the difficult decision was taken to adopt a palliative approach for her symptoms. She died a day later.

Discussion

Intravascular Large B-Cell Lymphoma is a rare subset of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL), affecting one in a million people [2]. First characterised in 1959 [3], it is known colloquially as “the great imitator” [2] due to its diverse range of presentations. It causes disease by a clonal expansion of lymphocytes within small blood vessels [1] resulting in end-organ damage. In retrospective analyses of case reports, around 90% of intravascular lymphomas are of B-cell origin. Unlike other NHL presentations, there is relative sparing of the lymph nodes [4].

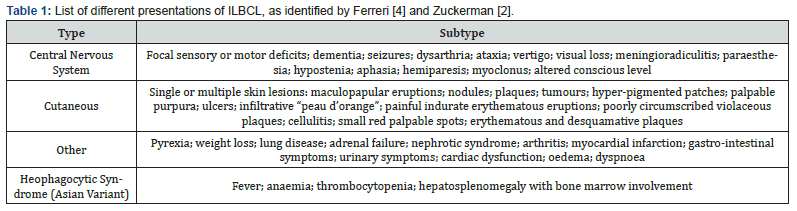

There are two forms of ILBCL, Western and Asian. The former presents, as in this case, with neurological or dermatological symptoms [4]. The Asian variant typically presents with multi-organ failure, pancytopenia, fever and bone marrow involvement.

Common manifestations of the Western variant are dermatological (nodes, plaques, nodules, purpura etc.) and neurological (Table 1). Neurological manifestations are present in two thirds of patients and can include mental status changes, seizures, paralysis, aphasia, dementia, motor deficits, neuropathies, paraesthesias and cerebral haemorrhage as well as many others [5].

One meta-analysis [2] published a table of presenting features from seven major studies. Of the 154 patients, 54% presented with CNS involvement, 45% with cutaneous involvement, and 41% with fever. Two of the most common biochemical findings associated with ILBCL are a raised lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) in up to 90% of cases, and anaemia in two thirds of cases [4]. There may also be a raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate, weight loss or fever.

The diagnosis of ILBCL is made by biopsy [6] of affected tissue, which typically shows malignant lymphoid cells in the lumen of the small blood vessels. One of the difficulties in diagnosing this disease comes from the intravascular location of the pathological cells, and the sparing of surrounding tissue making it difficult to identify pathological cells on biopsy (Figure 2). Bone marrow involvement with positive biopsies have been shown in about one third of patients [4]. There is also evidence that for all presentations, a biopsy of macroscopically normal skin is over 80% sensitive as a test for ILBCL [6], providing an alternative to brain biopsy.

Contrasting theories exist as to why these B-cells have a predilection for capillaries. One theory posits the pathological expression of certain cluster differentiation factors (CD11a and CD49d), which enhances binding to capillary epithelium expressing ligands for these factors (CD54 and CD106) [7]. The other suggests that an absence of surface molecules (CD29 and CD54) disrupts lymphocyte homing and leads to an aggregation in small vessels [8]. It may be that as well as understanding the pathogenesis of this illness, elucidation of any aberrant surface molecule expression may also aid the development of target-specific treatments.

If it is identified early, ILBCL can be treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy regimens. Typically, cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, oncovin, and prednisolone (CHOP) therapy is used –with rituximab in patients with specific B-cell markers. This shows better response and higher rates of remission than alternative regimes [9]. However, only 33% of treated patients survive 3 years [9].

Cutaneous presentations of ILBCL have a better prognosis than other variants [4]. Factors indicating a poor prognosis include elevated LDH and advanced disease with presence in several sites [10].

When considering differential diagnoses it is important to consider ILBCL as a well-recognised cause of stroke (ischaemic or haemorrhagic) despite its low incidence.

This case is important as it demonstrates a specific neurological presentation of ILBCL and illustrates the difficulty of making a diagnosis, as well as the aggressiveness of the condition. We should also not dismiss worsening psychiatric conditions as being a manifestation of the illness – however unlikely – given the close temporal association.

Learning Points

a) Intravascular Large B-Cell Lymphoma often presents with neurological symptoms (in North America and Europe) and is a rare cause of multi-territory infarcts.

b) The intravascular confinement of the clonal expansion of pathological B-cells causes end organ damage by ischaemia.

c) Diagnosis is made by tissue or bone marrow biopsy; but being intravascular it is usually made post-mortem.

d) Biopsy of macroscopically normal skin also has the potential to be diagnostic.

e) Raised LDH and anaemia are common findings.

To know more about Juniper Publishers please click on: https://juniperpublishers.com/manuscript-guidelines.php

For more articles in Open Access Journal of Case Studies please click on: https://juniperpublishers.com/jojcs/index.php

No comments:

Post a Comment